Crook contractor circumvents checks and balances to bilk borrower out of full funds disbursement.

The borrower in this case was a police officer in a city about 150 miles from the subject property. He was brought to Rehab Financial Group by an existing customer who also owned a contracting business with her husband. They had worked with each other on two prior projects RFG was not involved in. The borrower was qualified, and even though he was remote from the property, both the borrower and RFG relied on the contractor and their experience, given she was local to the project.

At the beginning of the project, the contractor’s husband convinced the borrower to open a joint bank account with him so all rehab funds RFG sent would go to this account. He claimed this was necessary to eliminate delays in any transfer of funds that could slow the project down. RFG was not aware the account information it was given was for a joint account with the contractor.

After closing, RFG began receiving inspection reports from an inspector it had used for several years who was local to the area. Based on these reports, RFG released funds for work completed at the collateral property, as evidenced by the inspection reports. In all, the full rehab amount of $122,000 was disbursed and an inspection report and pictures were sent showing the finished property with a “For Rent” sign in the window.

Problems

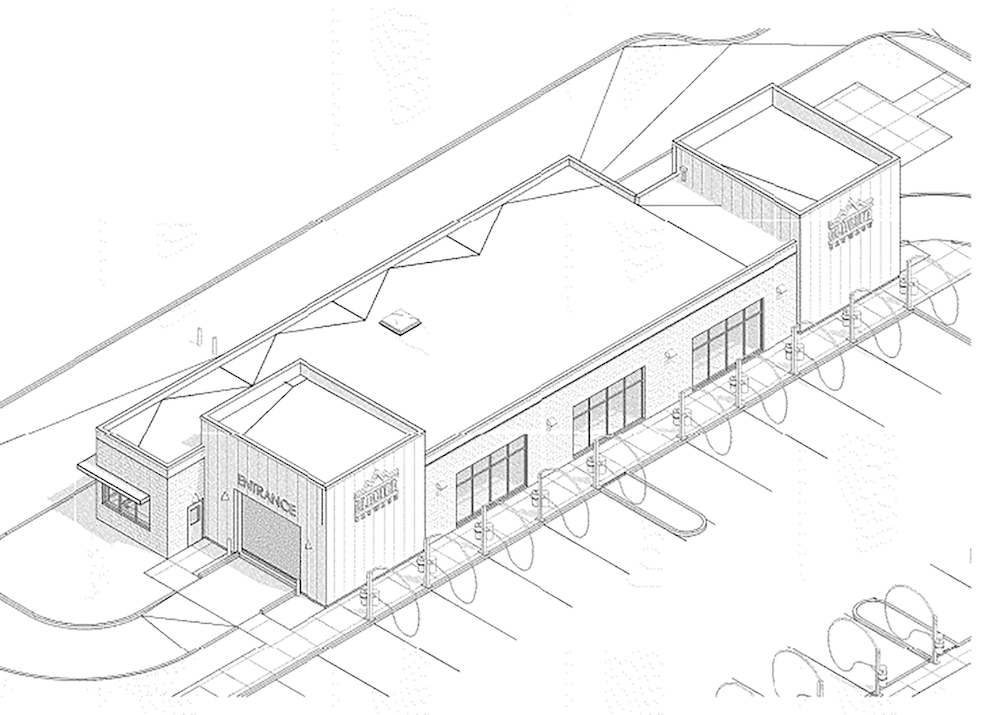

Shortly after, the borrower called RFG in a panic. He went to the property for the first time in six months and discovered absolutely no work had been done. The contractor could no longer be reached at any number and did not respond to emails, texts, or phone messages. As a last resort, the phone number on the “For Rent” sign pictured in the last inspection report was called. It turned out the pictures were of a different house with the exact same appearance as the collateral property. This identical property was in an adjacent town and had recently been fully rehabbed. The contractor for both properties was the same.

The inspector admitted to RFG that despite affirming in his reports that he had personally visited the property, he had not. He relied on the contractor to take pictures and send them to him; then he would then generate the report. RFG’s disbursements based on these reports were sent to the joint account the borrower had set up and subsequently stolen by the contractor.

The borrower was left with a house for which no work had been completed, but all the rehab funds were disbursed. RFG did an analysis to see if it was worth investing more funds to finish the property or sell it in its current state. In the end, it was determined that there was nothing to gain by spending the money to fix it.

Outcome

The borrower stopped paying and a foreclosure referral was made. Fortunately, the borrower was somewhat cooperative and was able to sell the property for slightly more than he had paid before the foreclosure process got very far. RFG and the borrower agreed to split the loss, with the borrower making monthly payments to pay back his share of the loss. By handling it this way, RFG was able to recover more than if it had spent the money needed for a foreclosure and sold the property in its “as is” condition.

Disappointingly, the inspector had no insurance for his fraudulent activities despite being HUD-approved.

RFG began litigation against the contracting business and the individual, as well as the inspector, for fraud. The case is still pending in the appropriate state court.

Since this event, RFG is very wary of doing loans with borrowers who are more than 60 miles away from the collateral property due to concern the borrower will not regularly visit to confirm what their contractor says is being done is actually being completed. In RFG’s opinion, the borrower is partially to blame for his failure to visit the property and being convinced to open a joint bank account with the contractor.

Leave A Comment