Answering this question is a critical first step in successfully launching your debt fund.

When launching a debt fund, you must understand when and how investors will enter and exit the fund. In addition to being one of the key mechanics behind the operations of your fund, it will be one of the questions investors and other stakeholders commonly ask.

Neglect in this area can lead to misallocation of profits and losses, incorrect distributions to investors, and issues with your audit, all of which can erode investor and regulator trust. With the guidance of your legal and compliance team, you must be proactive and intentional about structuring entry and exit appropriately before accepting investors into your fund.

Your fund’s operating agreement and term sheet are the documents that dictate how investors will be able to enter and exit your fund. The attorney who helps you with the formation of your fund will walk you through the different options and help formalize your decision in the agreement. Finding a legal partner who is specifically knowledgeable in both fund formation and the intricacies of the private debt industry is key.

Including your fund administrator and, if relevant, your external accountants (e.g., tax and audit) in the discussion is also important. Your fund administrator will record the investors entering or leaving the fund in accordance with the agreement, and your auditors will verify that capital transactions are properly recorded. One of fund managers’ most common pitfalls is lack of alignment with all necessary parties before operations begin.

Generally, one of the first decisions you’ll need to make is whether your fund will be open-ended or closed-ended. As with all fund formation topics, there are exceptions and hybrids. Funds can be customized in many different ways, but most funds start with these two well-defined options.

Close-Ended Funds

A closed-ended fund has a finite life and is commitment-based. Generally, over a period stipulated in the operating agreement (e.g., 1-2 years), investors will commit to a certain amount of capital that can be “called” over the life of the fund (usually 5-10 years). Typically, this capital cannot be withdrawn until the fund winds down. The amount of capital called from each investor will be pro-rata; therefore, each investor’s ownership percentage over the life of the fund will stay the same.

The process of letting investors in and out of a closed-ended fund is simpler than for an open-ended fund, because they all enter and leave the fund pro-rata on the same dates. Closed-ended funds have been historically popular for managers strategically investing in illiquid investments (i.e., private equity, venture capital, real estate equity).

Open-Ended Funds

A classic open-ended fund, on the other hand, has an open-ended term (usually limited only by ongoing investor funding and manager discretion) and accepts investor contributions when the fund manager chooses, generally at the beginning of each month or quarter. These funds often reinvest capital from paid-off loans. Some open-ended funds that reinvest capital from matured investments and continue to bring in more investor contributions over-time are referred to as “evergreen funds” due to their continuity and natural growth over time.

The process of letting investors in and out of an open-ended fund can be complicated, as detailed below.

Investment Company Determination. One of my previous Private Lender magazine articles explored whether your debt fund qualifies as an investment company (“Does Your Debt Fund Qualify as an “Investment Company?, Q4 2022, p. 16). The most important point for investment companies to remember is you will report a Net Asset Value (NAV) at fair value. This article assumes you have made the determination that your fund qualifies as an investment company.

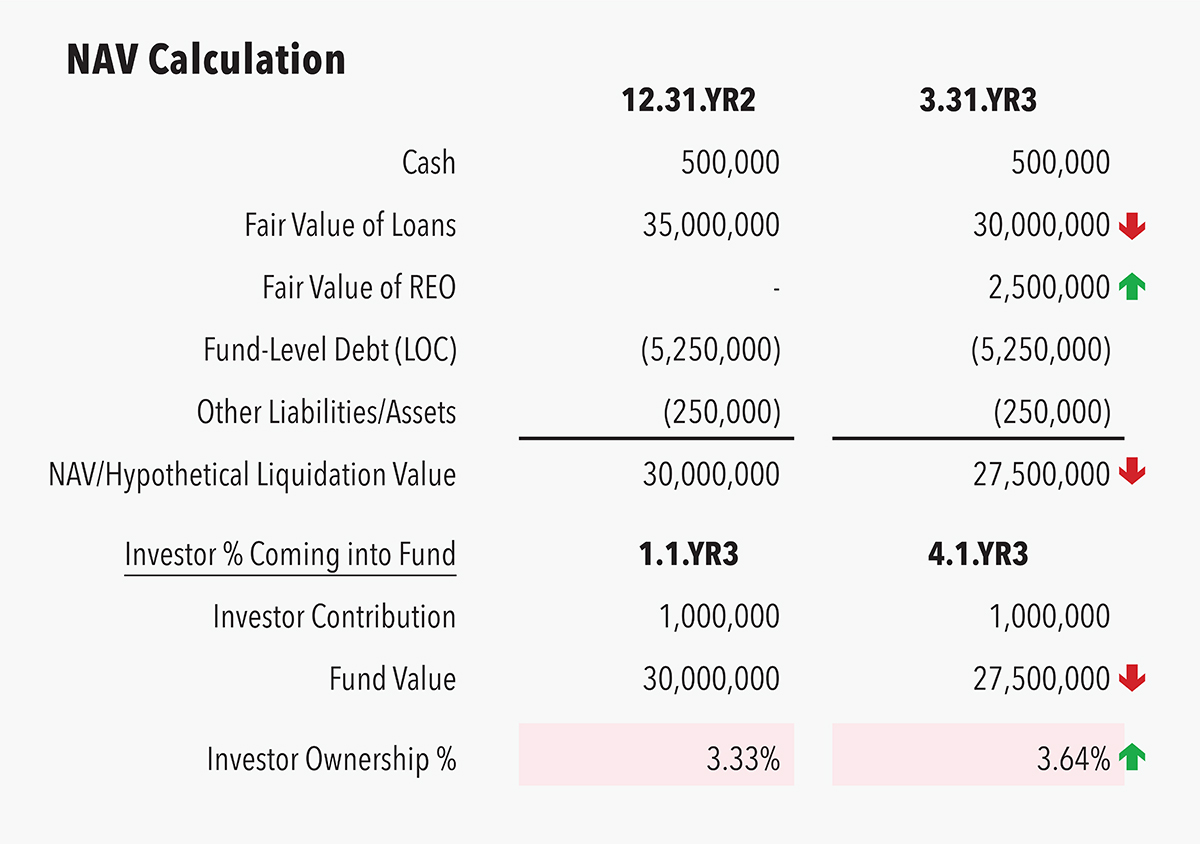

Striking a NAV and Hypothetical Liquidation. As noted previously, best practice for an open-ended fund that reports as an investment company is to allow investors in and out of the fund only on the date when a NAV for the fund has been struck. Generally, this is monthly or quarterly.

The fund’s NAV represents the fair value of all your assets, minus the fair value of all your liabilities, at a given point in time. A helpful way to think of the NAV is that it’s the value that would be received upon a hypothetical liquidation of the fund’s assets and liabilities.

The reason the NAV is so important on the date an investor enters or leaves the fund is that it ensures that all investors are “buying in” or “selling out” of the fund at its current value and, therefore, the correct price.

NAV can increase or decrease for any number of reasons. It may increase as cash is accumulated from interest payments from loans. It may decrease for accrued interest that hasn’t yet been paid on the fund’s line of credit. It may increase when you foreclose on a loan and end up owning a property that is worth more than the par value of your loan. More rarely, the NAV may decrease if the fair value of an underperforming loan decreases.

Note that it is common in the debt space for fund managers making short-term loans to target a constant NAV equal to the par value of the loans. They do this by distributing profits monthly and making a determination that the fair value of their loans are equal to par. This generally works in practice when loans are performing and GAAP (Generally Accepted Accounting Principles) books are being kept, but if you are structured to use this methodology, it is important for you and your investors to understand how the fund will be impacted if your NAV deviates from par (e.g., through a foreclosure, material change in comparable market rates, etc.).

For example, imagine you have an open-ended, investment company, debt fund that allows investors to enter the fund on the first of every quarter, as you strike a NAV at the end of each quarter. Let’s say you also distribute profits quarterly to return the fund’s NAV back to par. At the end of the fund’s second year, you have a NAV of $30 million, which also equals the value of your outstanding loans. In the first quarter of the fund’s third year, a $5 million loan goes into foreclosure and your fund takes control of the underlying property. Despite your rigorous underwriting and LTV standards, the value of the property is significantly less than the previous par value of the loan. A third-party expert indicates that the property is worth 50% of the previous loan, or $2.5 million. Now, let’s say a prospective investor wants to contribute to the fund at the beginning of the second quarter of the year. That investor is now purchasing into a fund that has a “hypothetical liquidation” value, or NAV, of $27.5 million, not $30 million. Because of this, their money will buy a larger portion of the overall fund and its future profits than if the loan was performing and the NAV had remained at $30 million.

Note that some funds use units to track and calculate investor capital (“unitized”), and others do not (“non-unitized”). It is a concept your legal counsel will likely consider and discuss with you as you set up your fund.

Additional Redemption Provisions. Often, additional restrictions are added around redemptions in open-ended funds. A variety of different provisions are used in practice, but some examples are requiring a period of 1-2 years of investment before being eligible to redeem, only allowing a certain percentage of the NAV to redeem in any given year, and general manager discretion. You and your team will need to determine what criteria are important to ensure you can appropriately manage liquidity.

A timely example of how these terms impact operations is occurring in the debt market currently. In January of this year, a Blackstone lending REIT with $69 million of value restricted investor redemptions in their open-ended fund. They did this when redemption requests went well beyond their 2% of NAV redemption limit. Imagine the impact that this sort of action has on all stakeholders in the fund.

Knowing how you will let investors enter and exit your fund is a critical first step in successfully launching your debt fund. Although it can seem like an overwhelming and daunting task given the many complexities and options, your legal counsel, fund administrators, and external accountants are great resources to lean on as you make your decisions.

Leave A Comment