Lender emerges with break-even scenario at best.

The information contained in this case study analyzes several aspects of a residential foreclosure. All confidential borrower information has been redacted from the case study to protect the borrower’s privacy.

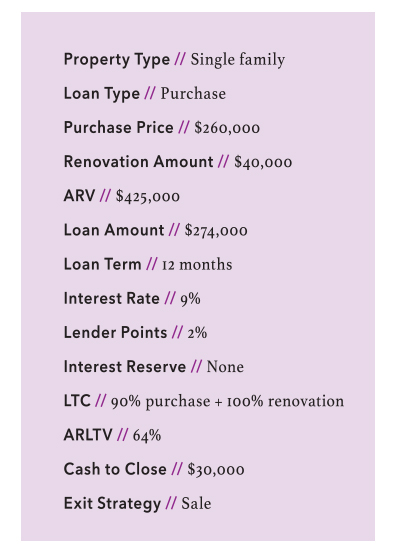

The borrower purchased the subject property from a private seller for $260,000. The borrower planned to spend $40,000 to renovate the property. The expected time from purchase to completion of the renovation was 90-120 days, and then the property would go up for sale. At the time the loan was made, comparable homes in the market area were selling within 14 days of listing on the MLS.

The borrower purchased the subject property from a private seller for $260,000. The borrower planned to spend $40,000 to renovate the property. The expected time from purchase to completion of the renovation was 90-120 days, and then the property would go up for sale. At the time the loan was made, comparable homes in the market area were selling within 14 days of listing on the MLS.

The borrower was a part-time real estate investor who had successfully completed one flip within 18 months of origination. The borrower also had a full-time job working at USPS earning $80,000 per year.

The borrower’s friend knew the seller of the property and that the seller wanted to close quickly. The borrower saw an opportunity and believed he could complete the renovation within 90-120 days and put the property on the market for sale for $425,000, generating a profit of $125,000.

Renovation Plan/Contractor

After closing, the borrower hired a contractor referred to him by a co-worker. The contractor, who was not licensed, told the borrower he did not need permits to renovate the property. The borrower did not inquire further. He did not check any references, verify the contractor had a license, or doublecheck whether a permit was required. He decided to proceed with this contractor.

The contractor told the borrower he needed an advance payment before starting the renovation. The borrower advanced 50% of the renovation amount, totaling $20,000. At this point, the borrower had spent $50,000 on this project: $30,000 at closing and the $20,000 advance payment to the contractor.

Timeline and Investor Reporting

After closing, the borrower communicated by phone and email almost daily to our servicing department, updating them as to his progress. He made his first payment, and he signed a contract with the contractor shortly after. The borrower made his second payment, and communication started to wane: We began receiving updates once a week and then every other week.

The borrower was now due for his third payment, which he made on time; however, there was no request for renovation funds. Our servicing department knew this was a red flag and checked the county website for permits. When no permit was found, they immediately scheduled an inspection of the property. Upon inspection, it was clear that no work had been done to the property.

Now, four months into the loan, our servicing department made calls and sent emails to the borrower that were not returned. Most important, the borrower did not make his next payment. The loan was then sent to our attorney who sent a Notice of Default (NOD). Within three days of receiving the NOD, the borrower contacted the attorney and offered a Deed in Lieu of Foreclosure also known as a DIL.

Now, four months into the loan, our servicing department made calls and sent emails to the borrower that were not returned. Most important, the borrower did not make his next payment. The loan was then sent to our attorney who sent a Notice of Default (NOD). Within three days of receiving the NOD, the borrower contacted the attorney and offered a Deed in Lieu of Foreclosure also known as a DIL.

Behind the scenes, our capital markets team was communicating with our end investor, taking valuable time and resources from the department. In addition to the resource drain and interest lost on the money paid out, funds were also paid to the foreclosure lawyer.

Financial Outcome

This case study is a perfect example of a borrower not being prepared or properly capitalized. As lenders, we do not want to foreclose, because nobody wins. Many borrowers think a lender profits when a foreclosure happens on a property of this type. After all, there was a healthy margin in the deal.

After we received the DIL, we set out to complete the renovations to extract the requisite value from the property. The renovated property did sell for $425,000, eight months after the DIL was signed. For us as the lender, that profit margin was expended on the inefficient process. After you add in the cost, time, and third-party expenses, at least we broke even; however, this is not always the case.

My first Red Flag would have been with the contractor. Not being licensed and telling the borrower that he did not need to get any permits would have me asking more questions before lending to him. Great example on how to be sure to vet a borrower.