Welcome to the world of financial engineering. Allow us to introduce you to the power and simplicity of some basic financial engineering techniques that will expand your business opportunities, allow you to entertain new lending strategies and help you understand that when Wall Street does financial engineering (referred to hereafter as FE), it is what we lay out in this piece, but with less transparency to the average investor.

At its core, FE is about leverage. It is also about allocating risk. It is also about risk mitigation.

When you own a cash-flowing asset, whether a loan or property, you can leverage that asset with borrowed money. Assuming the cost of the loan you are using for leverage has a lower interest cost than the net cash flow (sans principal) coming from the asset, then you should expect a higher return, all things equal, compared to not leveraging the asset. This is a very popular use for leveraging an asset, but usually entails much more risk than necessary and in a lot of cases requires a personal or corporate guarantee on top of the loan being provided as collateral.

The relevance to private lenders and lenders operating with a sophisticated website is apparent (website lenders are generally referred to as marketplace lenders). In this world where investors are searching for yield—and not just any yield, but yield with a risk level they understand—FE can be a market differentiator and give you and your firm a competitive advantage. If you have the ability to accurately design different return scenarios across risk and return profiles that incorporate the most sensitive variables to return, you will be way ahead of the average lender who says, “We offer our investors an 8% return.” Without context and details, investors have no idea what the assumptions built into that 8% return represent (a lot of the time there are no assumptions built into the return quoted).

Let us look specifically at leveraging debt secured by real estate. You can leverage it in two ways. The first is to put the secured debt up as collateral and borrow against it. This is called financial leverage. This is very common and doesn’t take much to understand other than you must read the leverage/loan agreement very carefully in order to know all the ins and outs of when the leverage is due and payable, cure rights, reps and warranties, etc.

Another way to leverage the debt asset is called structural leverage. In this approach you take the cash flows coming from the asset and direct them to different investors at different times. Investors who get most of the cash flows earlier generally get less of the interest generated by the underlying asset and suffer fewer losses if there is a default. Investors who get more of the cash flows at a later date typically get a higher interest rate than the previous investors, but in exchange they must suffer more—if not all—of the losses sooner and definitely prior to the previous investor. This structure is a simple senior/subordinate structure.

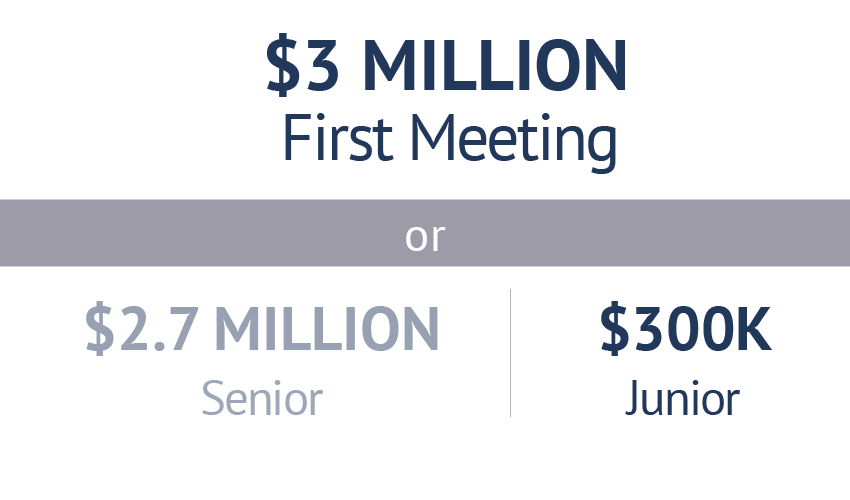

Structuring a $3 million loan, the basic idea is:

There are many variations that can be created between these two extremes. Also, the cash flow rules are a further layer of complication and can be structured differently from deal to deal.

FE allows for much more complicated structures than a simple senior/subordinate structure. If you ever get the chance take a look at a prospectus from a securitized mortgage deal; there can be up to a dozen or more tranches, which are referred to as classes (a senior/subordinate structure has two tranches). In addition the cash flow rules of who gets what and when can be as complicated as a physics calculation (just a little bit of an exaggeration).

The more complicated deals includes classes that only pay the investor interest or only pay principal, or only pay out a reserve fund if the credit performance of the pool is better than expected. All these tranches/classes have an economic value. FE is the epitome of “the sum of the parts is worth more than the whole.”

As most readers are aware, the rules have been changing for institutional lenders for the last few years (thank you, Dodd-Frank) and by implication the rules will change for everyone involved in lending. Even if you are not impacted directly due to some exemption, the rules governing institutions will eventually trickle through to sophisticated investors in that their expectations will be raised. For example, the commercial real estate bond market will soon be required to take on risk sharing (risk retention) as part of sponsoring the issuance of bonds (CMBS). This is euphemistically known as “skin in the game.” If you haven’t already, take a look at the various ways CMBS sponsors can do risk retention. The point being that FE allows you to have skin in the game while getting paid for it and at the same time returning a well-structured yield to your investors.

In fact, we believe the risk retention rules are a great opportunity to come to private and internet-based lenders. The market opportunity to show that you eat your own dog food will be huge in the coming years. We also believe the firms that structure a large part of their business around the risk sharing concept will have a competitive advantage over firms that just buy and sell notes. Not only can you make your investor customers happy, you can also start to create another prized outcome of FE—being classified as an asset manager as well as a fund sponsor. You will be creating enterprise value for your business beyond the yields your investments generate. The market opportunity is huge, and there are unlimited ways to slice and dice the market. Firms will exploit the opportunity to the level of their ethical and business practice and FE acumen.

We have attempted to make this piece more of an intro piece (notice the lack of math calculations or even complex charts) in order to showcase our enthusiasm for the opportunity awaiting the market. Inasmuch we support the current crop of online lenders, we feel that as of yet no one has fully capitalized on the formula of risk alignment (or sharing) with their investors—a simple but powerful structure that will truly be a game changer in the marketplace lending world.

Perhaps in future articles we can drill down further. We in no way have all the answers, but given our current understanding of the market, the members of the AAPL should be a thriving and growing community with some of the firms creating a regional, if not national, presence.

Michael O’Meara and Loren Picard’s article originally appeared in Private Lender magazine: September/October 2016

Leave A Comment