Series Note: This is the second article in a series about operational risk in construction and renovation lending. The series, written from the perspective of a chief lending officer, examines examples of operational risk, addresses common misperceptions, and proposes emerging best practices and recommendations for lenders striving to scale their portfolios responsibly. The first article, “The Blind Spot,” appeared in the Fall 2024 issue of Private Lender. It set the stage for why “operational risk” matters to construction or renovation lending.

Operational risk is greatest during the draw management process when the property’s loan-to-value fluctuates and unforseen challenges crop up during construction.

The draw management process can help you defend again operational risks in construction lending. In particular, following draw management best practices help you guard against perils that can occur in some of the early stages of renovation.

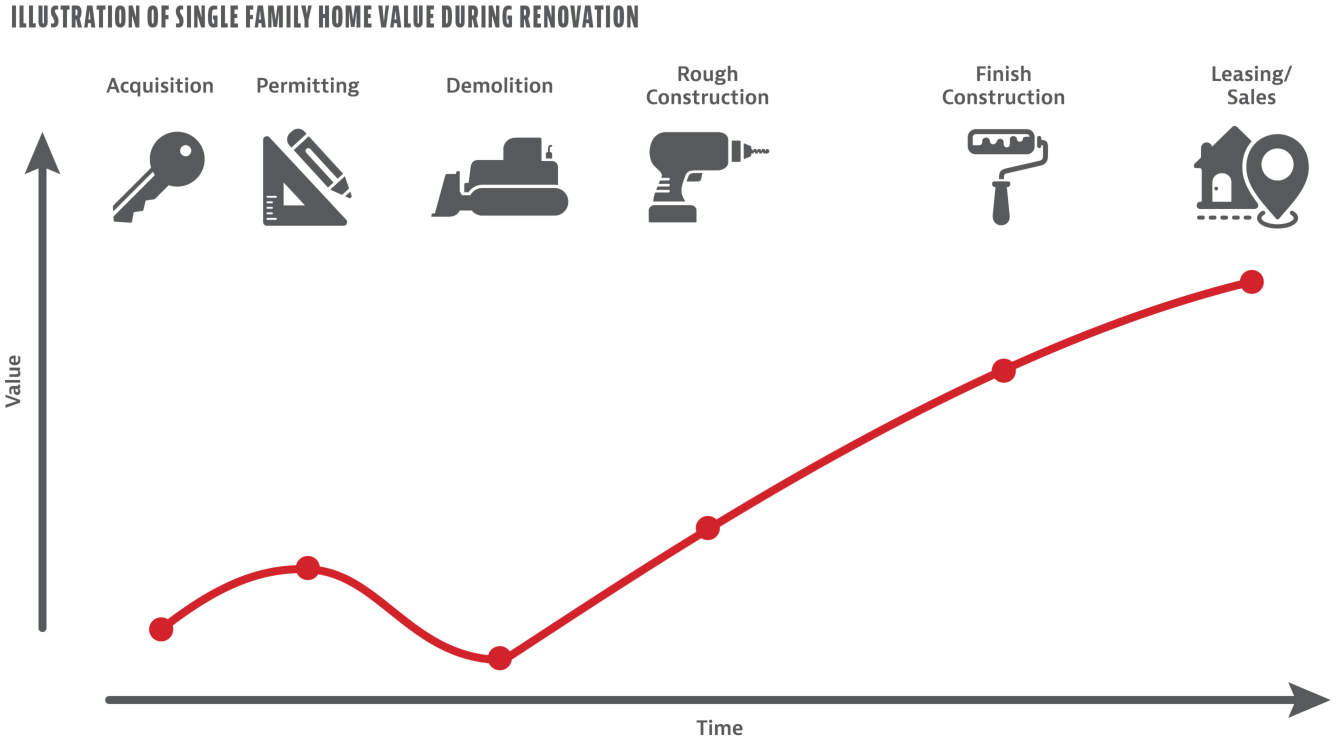

The accompanying figure shows how a property’s value can rise during the various stages of renovation.

Unfortunately, during a renovation, expected property value does not rise continually “up and to the right.” There is a danger zone where expected property value dips for some projects, typically from demolition through rough construction completion. This makes sense intuitively because the renovation involves destroying the collateral to build back better (hopefully). Beyond an implied instability in the loan-to-value ratio, there is a higher associated cost of taking back an incomplete property during that phase. Further, projects may face unforeseen circumstances at any time, ranging from unexpected requirements (e.g., retaining wall, sewer main repair) to events (e.g., extreme weather) that cause damage.

Loan-to-value is a dynamic concept in construction lending. Ensuring construction holdback capital is deployed proportionately through the project’s completion is a key operational risk mitigant and the responsibility of the draw manager.

What is Draw Management?

Funds paid at closing are generally used for acquiring the “as-is” property; the remainder is retained in a “holdback” that is held back (true to its name) for use during construction, enabling the transformation of the property to its highest and best use or after-repair value (ARV). Holdback funds are released from the total loan commitment as the project progresses via borrower draw requests, which the lender must approve.

Essentially, every draw in a construction loan is a “mini” underwrite, not of the sponsor but of the loan’s current state vis-a-vis the underlying property’s unique path to completion.

Let’s dive into four fundamentals of construction draw management.

#1. Work in Place Before Money Out

The “work-in-place” standard is a basic tenet in renovation and construction lending. It refers to measuring the project’s hard cost completion in terms of completed labor and materials that are physically installed on-site (i.e., “in place”). As a general rule, holdback releases should align proportionally with project completion.

Measuring hard cost completion involves inspections of progress (i.e., draw inspections). Inspections require detailed project context and expertise. Inspectors may perform their work on-site or remotely, potentially facilitated by technology that enables borrowers to submit photo or video evidence of progress. Consistent inspections and informed draw reviews allow lenders to identify potential issues early, mitigating risks before they threaten the project’s long-term viability.

To maximize operational risk mitigation, inspections should require a qualified inspector who knows the project’s current scope, budget, and starting state as a baseline. Sharing the appraisal with the inspector is a best practice that allows the inspector to reference photos of the property’s starting condition and the description of scope. No inspector or inspection is perfect, of course; the goal is a reasonably informed opinion obtained through a reliable and systematic examination.

Ensure an independent judgment that minimizes misalignment in the determination of completion. Sometimes inspectors can become too cozy with a borrower and, in extreme cases, even outright collusion occurs. Lenders with in-house inspectors ideally separate that role from the borrower relationship manager to avoid undue influence.

Avoid blurring the lines between what the inspector recommends and the lender approves so you are aware of significant variances in how your draws are approved compared to the project completion rate. Growing variances can mean holdback funds are being released ahead of sufficient completion and may expose you to significant operational risk if you have to take back the property. Further, watch for completion numbers in inspection reports being “adjusted”; this may be warranted but should be documented and monitored to ensure approvals are achieving risk mitigation.

Monitor for errors or fraud, especially if you allow borrowers to submit their own photos or videos. Known fraud risks include photos taken at a different unit or job site or photos taken of photos. Inspectors are also human and can simply make mistakes, including not noticing things or more egregious errors like inspecting the wrong location (or even being tricked into doing so).

There are two notable exceptions to the work-in-place standard.

One common exception is soft costs (e.g., architect fees and permitting costs). Although no observable progress is made, soft costs are part of every project and necessary to completing a project. Most lenders allow draws to include soft costs, but they release funds only proportionate to the hard cost completion. Some lenders will release soft costs in full as incurred for repeat borrowers who are in good standing. In either case, approving soft costs causes a rising variance in the lender approval versus hard cost completion. Again, this may be fine but it should be monitored.

Other common exceptions are material deposits or off-site storage, which present a unique challenge. In these cases, there is no observable progress in completion, and the materials have not been delivered to the site yet. However, withholding funds for deposits can delay the project if the borrower cannot cover the upfront costs. As such, some lenders will make a partial allowance for materials deposits, for example, up to 50% with proof of invoice and payment and the remainder once there is proof of invoice, payment, and delivery on-site.

Other lenders are stricter and require the delivered materials to be fully installed before the remaining holdback funds are disbursed. Even releasing funds after delivery is a challenge if trust is low, given the borrower could deliver materials like lumber or appliances to one property for the inspection and then relocate those materials to another property. Similar to soft costs, these exceptions create a rising variance too.

#2. Beware of Unpaid Work

Even if an inspection confirms work was completed, there is residual operating risk if the construction vendor or supplier involved was not paid. This creates the potential for mechanics’ liens to be filed, which could result in the lender being “primed” and losing lien priority on the property to these parties. Lenders and their borrowers may not know about all vendors or subcontractors working on their project, but they are still subject to their mechanics’ liens.

Signed lien waivers are one mitigation tool for managing the risk of mechanics liens. These include conditional progress lien waivers prior to payment and unconditional progress waivers after payment has been made. If the right statutory form is signed by the right party in the right amount, these documents can help mitigate risk from vendors known to the borrower or lender. “Known” is a key word, however.

Requesting proof of payment for the invoices in a draw request is another mitigation tool. Ensuring funds were disbursed by the borrower or general contractor is critical, because funds sometimes are withheld for various reasons, ranging from exerting leverage over subs to contract disputes. Collecting conditional progress waivers and corresponding proof of payment is a respected approach.

Lenders also can use title searches to check for any undisclosed liens or outstanding claims on the property. This search may be done as a stand-alone or in conjunction with signed lien waivers. Further, title endorsements can be obtained that provide the added protection of insurance but with additional cost and delays to the approval process. Renovation often involves only title searches, whereas new construction likely involves title endorsements and lien waivers (and doubly so for larger budgets and project complexity).

That said, be sure to tailor any risk mitigation to the situation. For example, asking for signed lien waivers from a self-performing borrower (i.e., no vendors hired) provides little to no protection since the lien claim filed by a borrower against his own loan would be unlikely to hold up in court. Similarly, accepting lien waivers signed by the borrower when there is an independent general contractor vendor or signed by the general contractors for their subs’ or suppliers’ work does not mitigate lien risk either.

The bottom line is that lien waivers used inappropriately are unlikely to provide protection. Worse, they can damage the customer experience and your credibility in the market.

#3. Monitor the Project Budget

Knowing the original construction budget size, its uses in terms of line items, its sources of funds, and any changes to it along the way is critical. The budget provides a proxy for measuring project scope, a baseline for measuring its progress, and insights into the borrower’s judgment.

Throughout the construction project, there are often requests to “reallocate” funds and sometimes expand the construction budget through change orders. These requests are invaluable signals about what is happening on the ground. While it’s tempting to say “not my problem” as a lender, these changes can become your problem quickly if they imperil a borrower’s ability to complete the project.

Moreover, these changes can inform you about what is happening on the ground and may provide a reason to dig deeper into pending draws. For example, budget changes might reflect a dynamic scope of work, such as the addition of a bathroom or even an ADU. Changes often suggest the project requires more time, rendering the original schedule inaccurate. Changes could indicate shifts in the market; for example, the cost to build a four-bedroom house no longer aligns with the original plan or anticipated value.

Remember, follow the money. Keeping an auditable history of the original budget and its evolution is foundational to managing the operational risks for active construction. Better yet, understand what the underlying drivers are, from replacing estimated numbers with contracted rates to unforeseen circumstances (e.g., hidden damage) to new requirements from a code inspection (e.g., retaining wall) to expanding project scope (e.g., adding square footage or structures).

Second, include a contingency line item (often 5-15%) in the budget because renovation and even new construction involves unknowns. If you include a contingency, keep track of which line items are growing and monitor them for excessive consumption that occurs too early in the project; that may indicate an inadequate budget or unforeseen circumstances.

Third, avoid approving overdrawn line items. But the money must come from somewhere. The source could be from contingency, reallocation from another line item, or additional borrower equity for an expanding budget. If you’re drawing from contingency, consider tracking as a reallocation so you monitor which line items are growing.

#4. Compare, Compare, Compare

Look beyond the current draw. How does the velocity of draws and project completion compare to the reported completion date and/or loan maturity? Stalled projects without recent draws are often the projects with a higher operational risk. When borrowers are submitting draws, have them reconfirm or update their estimated completion date.

Lenders should anticipate consistent progress toward completion, making delays a clear warning sign of potential risks to meeting the loan’s maturity date.

Relatedly, before releasing final holdback funds, confirm there is a closed permit and certificate of occupancy, if applicable. Keep in mind that a temporary certificate of occupancy (TCO) can be rescinded. If the project is not final, push to understand why.

Despite best efforts , challenges will happen. Lenders can bring valuable perspective and expertise to the table informed across a variety of loan types, project sizes, municipalities, and construction-related issues.

Automation and predictive analytics powered by software and artificial intelligence/machine learning are increasingly in use and are changing the game for construction lenders in terms of productivity, execution speed, and customer experience.

Keep in mind, focusing on customer experience to an extreme exposes you to a higher risk of losses or losing capital providers, while focusing on risk mitigation to an extreme leaves you at risk of not attracting or retaining customers. Striking the right balance is an active sport.

Engaging early, often, and proactively increases your success and reduces losses, whatever path your loan may take. It is better to work out solutions while there is money remaining in the holdback or while the borrower has equity funds still available. In short, keep yourself in the conversation.

John Adractas is the CEO and co-founder of TrustPoint AI. A serial entrepreneur and founding product leader in vertical SaaS and enterprise analytics across five companies, he previously worked at Google and Simplee (now the healthcare division of NASDAQ: FLYW). Adractas earned an MBA from Harvard Business School and a bachelor’s degree in mathematics and philosophy from the University of Pennsylvania.

Leave A Comment