Government intervention in the housing and lending markets through eviction and foreclosure moratoriums is impacting private lenders’ ability to deploy capital and originate loans.

To say things have changed in 2020 would be the understatement of the century. Efforts to limit the spread of COVID-19 have impacted all facets of life.

Real estate and real estate finance have experienced a bit of roller coaster ride since the initial lockdowns were instituted. Some asset classes such as retail, office, and hospitality continue to be hit hard. But residential real estate, both owner-occupied and investment properties, has benefited from what appears to be a structural shift in the way people want to live. Remote working and learning have highlighted a need for more space. Demand for residential loan origination, after a bumpy credit markets shock in late March, is booming.

Homeowners looking for more space and renters who can afford to buy are driving demand for single-family homes in markets nationwide. This, coupled with historically low interest rates, has resulted in a veritable home buying frenzy. The impact is also being felt in the residential investment space, with flippers seeing their completed projects sell rapidly, often with multiple offers. Flippers do face significant competition for deals, however, and foreclosure moratoriums remove a key source of supply of new projects.

In the rental markets, a similar shift is occurring with demand for single-family rental homes outpacing demand for traditional stacked apartments. The theory is that residents cooped up in their apartments want more distance from neighbors and more space to work and attend school from home. Prompted by increased demand for their properties, rental investors are actively seeking to grow their portfolios.

Although these trends represent a tail wind for both investors and lenders, government intervention in the housing and lending markets has started to create a drag on the velocity with which private lenders can deploy capital and originate loans. Let’s take a closer look at the impact of the two interventions: eviction and foreclosure moratoriums.

Eviction Moratoriums

To assess the impact of local eviction moratoriums on lenders, you first need to assess the impact to the owner/landlord. Eviction is the primary remedy a landlord has to enforce their right to collect rents from tenants. With rental income being the key revenue source for landlords, a nonpaying tenant quickly erodes the P&L of a property, driving the landlord to dip into reserves and income from other sources to pay property level expenses, including debt service and property taxes.

Although the intent of these moratoriums is likely in the best interest of the general public, meaning putting people into the streets in the midst of a global viral pandemic is probably a bad thing, there are unintended consequences. Roughly 60% of the rental homes in the U.S. are owned by landlords with 10 or fewer properties, so the impact of these eviction moratoriums will be felt differently. Smaller owners will likely be disproportionately impacted versus large institutional landlords. Well-capitalized owners with low leverage, high levels of liquidity, and varied sources of capital should be able to manage through the moratoriums relatively unscathed, because they are often capitalized in a way that provides optionality and longevity.

What does this situation mean for private lenders? There are two key implications for those lending on rental properties. One is related to future cost of capital, and the second is related to demand for loans.

Lenders making rental loans should anticipate and plan for increased requests for forbearance or payment deferrals from landlords due to loss of rents. Additionally, it would be reasonable to expect an erosion in performance of the loan book in terms of late payments and delinquencies. Both have the potential to impact lender cost of capital, as the weakening performance of the book could translate into higher borrowing costs over time.

There is also the possibility of reduced demand from landlords for loans on rental properties. In the face of limited rights as a landlord, it remains to be seen whether rental ownership loses its luster. As a lender, you hate to acknowledge it, but owners with little to no leverage are best positioned to weather an environment where eviction is not allowed. Will the regulatory intervention spook rental investors in such a way as to steer them away from borrowing over the long term?

Both a higher cost of capital from weakening book performance and reduced appetite for loans by skittish landlords create a drag on a lender’s ability to put out capital at scale.

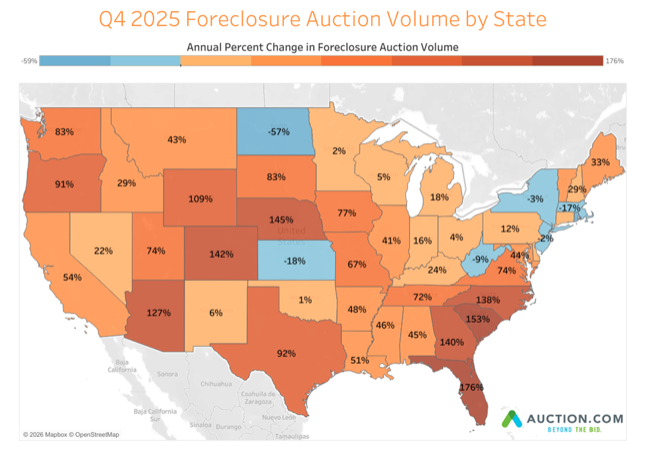

Foreclosure Moratoriums

As with the eviction moratoriums, the intent of imposing foreclosure moratoriums was likely good—to keep people in their homes during a pandemic. However, some states have imposed broad foreclosure

moratoriums that do not include carve outs for loans made on investment properties. While it appears that agency lenders for owner-occupied properties have not skipped a beat in lending to homeowners and homebuyers, the impacts on the private lender sector could be far more negative, at least in the short term.

Whereas eviction is the primary remedy landlords can use in the event of tenant nonpayment, foreclosure is the primary mechanism available to lenders in the event of borrower default and nonpayment. If a jurisdiction nullifies the primary remedy a lender has in enforcing the loan contract with a borrower, why would a lender continue making loans in that market? Private lenders do face greater risk in making loans when foreclosure is off the table.

When making a credit decision, lenders consider several factors, including the customer, property or project type, and location, to name a few. To mitigate the risks associated with each deal, private lenders have a few levers to pull from leverage and rates to points and forms of guaranties to ensure adequate compensation for and mitigation of the underwritten risk. None of these levers adequately addresses the risk that accompanies restrictions on using foreclosure.

Lower leverage would normally provide some measure of protection because foreclosure allows a lender to get to the asset with less exposure in a downside scenario. Reduction in leverage becomes an irrelevant tool for mitigating risk when foreclosure is not an available remedy. Higher rates are a mitigant only so long as a sponsor has an incentive to keep paying. The threat of foreclosure and loss of the property provide that incentive. Without foreclosure as an option, this too is irrelevant. Foreclosure moratoriums result in the removal of a lender’s ability to enforce the loan contract and, ultimately, drive lenders to take a hard look at whether there is any reason to continue making loans in a given market. Lack of financing in a market drives property values lower over time.

Foreclosure moratoriums have a direct impact on a private lenders’ ability to deploy capital via new loan originations. First, in states where moratoriums are broadly instituted and do not carve out investment properties, lenders are likely to slow or even stop lending while the legal landscape evolves. Second, residential investors often use foreclosures as an important source of properties to feed their fix-and-flip or fix-and-hold businesses.

With fewer foreclosure properties available, borrower demand for new bridge and rental loans from private lenders will slow, again reducing the velocity with which lenders can originate. Foreclosure moratoriums cause a trickle-down effect that ultimately reduces the capital a lender has available to deploy in new loan originations. Although it’s a simplification, when a lender cannot foreclose to recapture some or all of the previously deployed capital, eventually they cannot continue making loans. The follow-on effect of lenders not lending is downward pressure on property values.

Although the duration of the impacts of these regulations remains unknown, lenders can take measures to address risks associated with rental lending and lending in markets where broad foreclosure moratoriums exist.

Lenders could consider taking interest or P&I reserves for the time horizon they believe the impacts will last. Another option is to tighten the credit box in foreclosure moratorium states, limiting lending to existing proven customers and select new customers with strong track records, good credit, and strong liquidity. None of these solves for the full spectrum of new risks private lenders need to navigate. But developing an informed, medium-term view to guide credit policy and strategy that enables new loan originations seems like the best place to start.

Leave A Comment