Banks are moving away from DSCR, and private lenders should consider doing so too.

For many years, banks have used the Debt Service Coverage Ratio (DSCR) to assess risk regarding a borrower’s ability to make mortgage payments after subtracting normal expenses from income. This ratio is crucial to determining a borrower’s ability to repay a loan, but it does not tell a financial institution about the impacts to its bottom line if it must foreclose on the property and sell at less than market value. As you may remember, this was an oversight that contributed significantly to the 2008 housing crisis.

What DSCR Doesn’t Address

Before 2008, the larger the Debt Service Coverage Ratio, the more comfortable the bank felt making a loan. For example, let’s presume a borrower is considering applying for a $650,000 bank loan amortized over 20 years at 4%. The monthly payment would be about $3,939 per month. If the apartment building grossed $8,000 and the normal expenses were $3,000 per month, the Net Operating Income (NOI) would be $5,000 per month. The DSCR would be 1.27 ($5,000/$3,939). Of course, the bank would also look at the Loan to Value (LTV) in conjunction with the DSCR. Presuming the value of the apartment building was $1,000,000, a 65% LTV loan would be acceptable to most banks.

In previous years, many banks were willing to allow a DSCR as low as 1.00, meaning the NOI exactly covered the bank’s monthly payment. The problem was that in a market crisis with borrower income shrinking, exactly covering the net operating income wasn’t enough and defaults skyrocketed.

Following the Great Recession in 2008, banks’ solution to protect themselves was to raise the DSCR to 1.15, then to 1.25, with most finally settling on 1.35. This severely constrained many borrowers’ ability to finance their real estate projects. They either had to come up with more cash, negotiate for a longer term (25- to 30-year amortization periods) or request a lower interest rate due to the supposed lower overall default risk to the bank. These compromises allowed borrowers to borrow the total amount they initially needed while still meeting the more stringent 1.35 DSCR.

While from many perspectives this would “fix” the DSCR problem, the issue is the bank was still at the same LTV. In fact, you could argue the bank was not compensated for the benefits bestowed upon the borrower in the form of a lower rate and longer amortization period.

Just because the borrower met the new DSCR requirement did not put the bank in a safer position if default occurred due to another market crisis. It only addressed the borrower’s ability to make the monthly mortgage payment. DSCR does not address the LTV risk for the bank or give the bank a rate of return (ROR) should the bank need to foreclose on the property.

Added to this, as banks were dropping interest rates and stretching amortization periods to help borrowers accommodate high DSCRs, they were also forced to allow higher LTVs. Before 2008, banks were willing to lend at a high LTV. Historically, 60-65% was the norm; however, increased competition between banks pushed LTVs even higher to gain an advantage with borrowers. While the lower interest rates appeared to assist the bank with risk due to the relatively low (historical) mortgage payments, when market prices dramatically decreased, many lenders were faced with borrowers who were upside down on their loans.

From all perspectives, DSCR was no longer a good assessment of risk because it only provided for a fair-weather scenario where the borrower remained the property owner.

Enter DYR

Enter the Debt Yield Ratio (DYR), which allows financial institutions to assess risk for when they must foreclose and possibly sell below market value. Although this ratio has been making the rounds with banks, many private lenders are still unaware of it—to their detriment. This ratio allows institutions to forecast scenarios in which the borrower’s net operating income is stressed.

For example, in a booming economy combined with low interest rates, NOI drops considerably. The main reason is the confidence level of buyers needing only a marginal return and the perceived lack of risk, especially with desirable properties in excellent locations.

For example, a four-plex in Sausalito, California, was sold at a paltry 1.76 capitalization (CAP) rate. The rents were at market level. If the economy suddenly turns negative, the value of this property could potentially plummet as would-be investors would command a much higher ROR (i.e., a high CAP rate).

In this scenario, DYR effectively shows the bank what rate of return it would earn if it had to foreclose. The annual NOI for the apartment building was $60,000. Since the loan request was $650,000, the DYR was a healthy 9.23%. Although no bank wants to foreclose, it still must face the fact that there are times when it will need to. When CAP rates are in the 4-6% range, a DYR above 8% gives the bank some leeway should it need to sell the property at less than fair market value and recoup its entire loan with no loss.

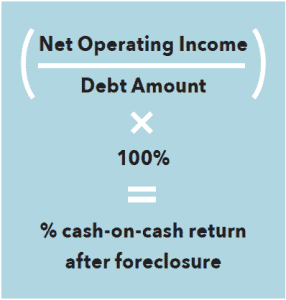

The ratio itself is simple:

You can see that although most real estate investors focus on CAP rates, the DYR zeros in on the ROR the bank will earn upon foreclosure. The DYR also ignores the interest rate the bank charges as well as the amortization of the loan. The reason for this is the bank is focusing on what the expected income derived from the property is compared to its loan. It is strictly a ROR function.

The DYR is vital in today’s low interest rate environment. As interest rates dropped over the previous 10 years, values substantially increased. Lenders do not want to get caught in situations where, all other factors staying the same, the fair market value plummets due to increased interest rates. Thus, the DYR focuses in on the ROR the lender would receive if it were to receive the property upon foreclosure.

Of course, if interest rates rise, the bank would have liked to have had a larger DYR, but it is similar to an investor being happy with a bond that is locked in at 10%, even if interest rates rise to 12%. The main drawback for lenders using the DYR has more to do with closing loans. The higher the DYR, the less likely the bank will be competitive with terms they can offer the borrower, mostly having to do with how much the bank is willing to lend against a specific property.

Of course, if interest rates rise, the bank would have liked to have had a larger DYR, but it is similar to an investor being happy with a bond that is locked in at 10%, even if interest rates rise to 12%. The main drawback for lenders using the DYR has more to do with closing loans. The higher the DYR, the less likely the bank will be competitive with terms they can offer the borrower, mostly having to do with how much the bank is willing to lend against a specific property.

Advantage for Private Lenders

Where is the advantage to private lenders in all this? By requesting a high DYR, the bank will automatically limit its LTV. As banks get skittish, they will continue to raise their DYR. One large bank has already increased its DYR to 11%. Factors that may lower the bank’s DYR may be the location of the real estate. Desirable and stable areas may command a lower DYR. Of course, these same areas also command lower CAP rates as well.

The opportunity for private lenders is that the higher the DYR the bank requires, more borrowers will need private financing. The banks simply will not be able to provide the needed capital due to constraints applied by a high DYR.

Of course, private lenders should look at their own DYR they impose on borrowers. Most do anyway because that is the nature of private lending. If the lender forecloses (and retains the property), the DYR suddenly becomes the ROR on the loan. Private lenders have more flexibility in assessing what DYR to apply, and each situation will be different depending on location, asset type, condition of the property and other factors.

Know the Exit Strategy

Although banks using high DYR thresholds can open more loan opportunities for private lenders, there can also be drawbacks.

The main question for private lenders is “What is your exit strategy?” As banks get more conservative with their underwriting and have stricter ratio requirements, private lenders need to make sure the borrower will be able to meet the refinancing bank’s guidelines or see that the borrower plans to sell the collateralized real estate. Just as rates may vary when considering higher versus lower LTVs, bank rates may vary based on higher versus lower DYR. This makes sense when considering that banks price their products based on risk.

From a borrower’s perspective, negotiations will now have to be looked at from not only the CAP rate and the DSCR rate but also the DYR. Borrowers who can make a larger down payment should consider all three ratios. A little extra down payment may go a long way toward receiving attractive terms from the bank or private lender.

As a private lender, if you are not already considering your own or a prospective bank’s DYR when transacting a loan, it is a detriment to your bottom line should another downturn occur. The DYR, among other considerations, allows all lenders to better navigate and survive the vagaries of the real estate market and economy.

Leave A Comment