Lenders must help borrowers understand the intricacies of draw management for their rehab projects, including how draws are tied to budgets, timelines, inspections, and other common issues.

Draw management is a significant factor in whether a rehab project is successful. The process of draw management starts before the loan is closed, when a repair list and timeline for various phases of the project are agreed upon. Rehab lenders hold the rehab funds for a project in reserve after loan closing. As borrowers complete work on the property according to the agreement, the funds are released.

The key here is the specificity and preciseness of the repair list. The more precise the repair list is, the easier it is for the lender to release funds.

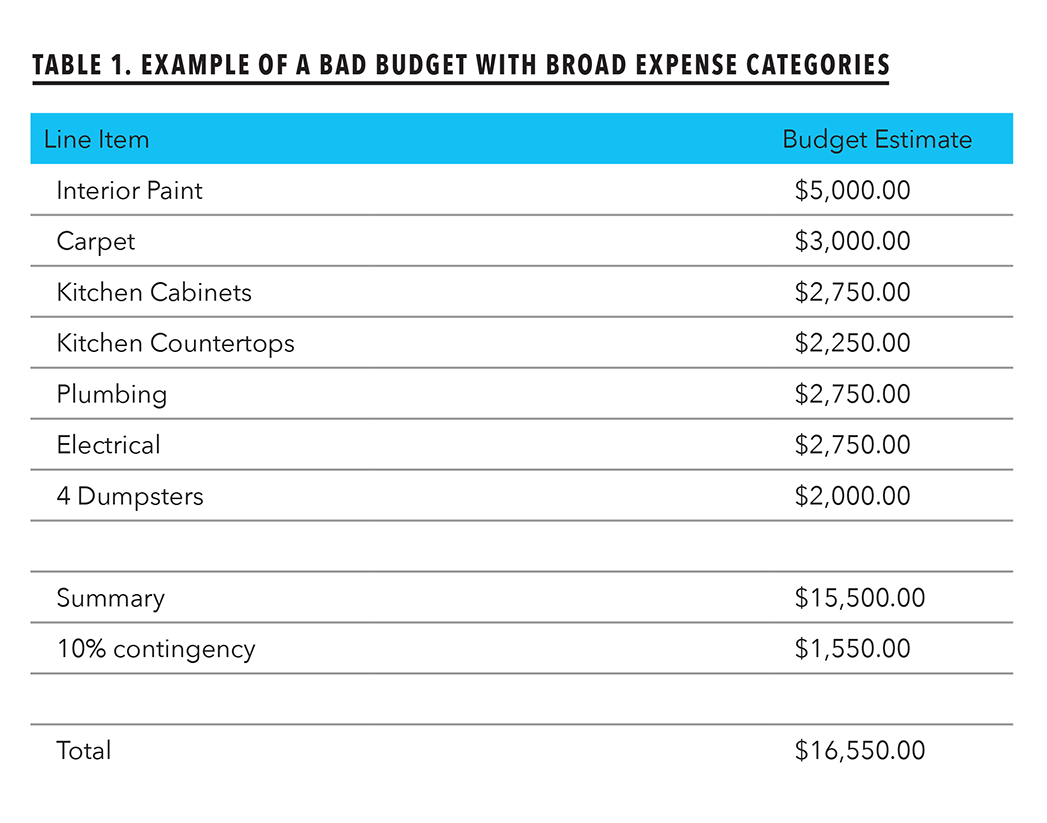

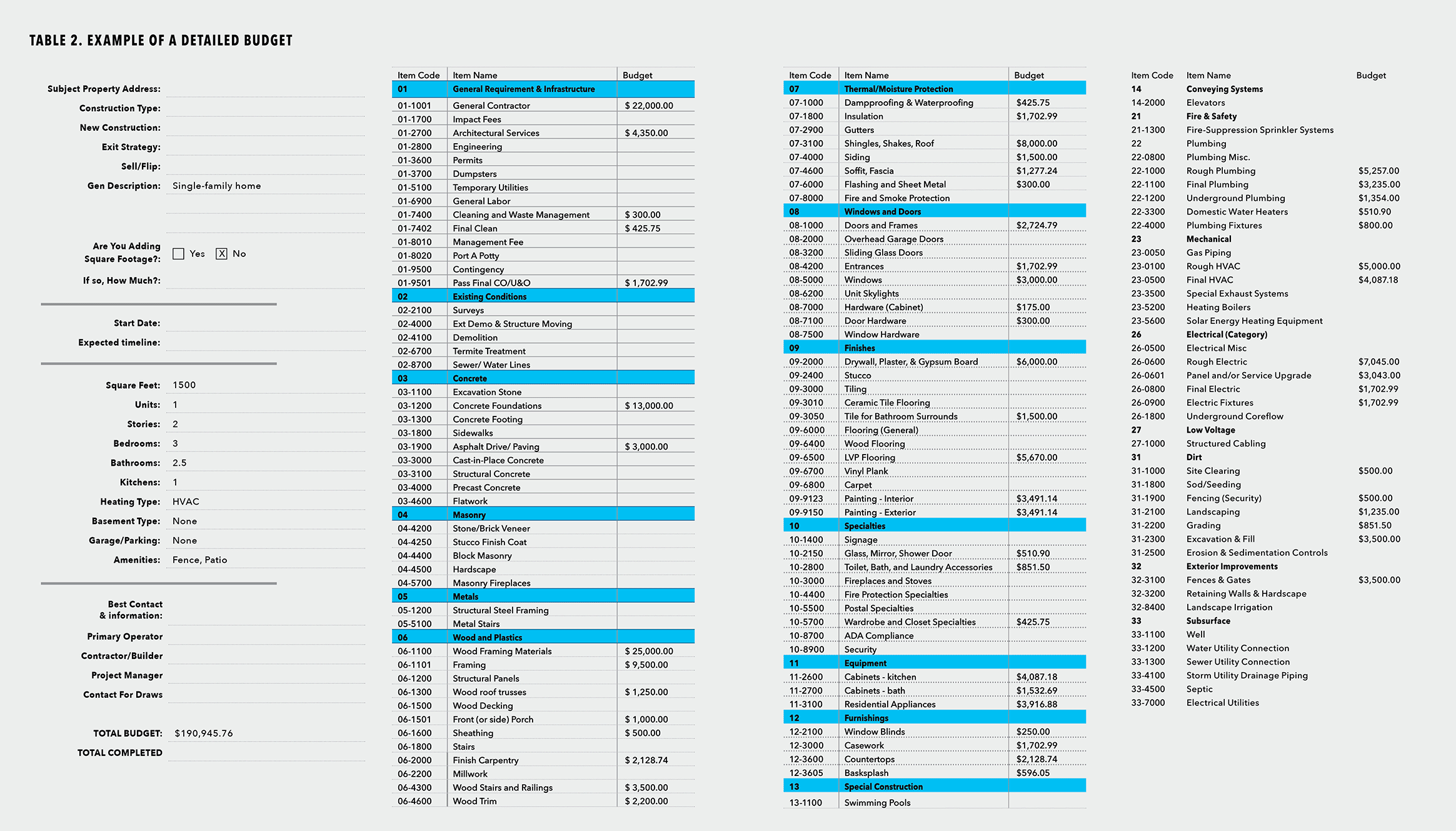

Budget Do’s and Don’ts

The budget must provide as much detail and granularity as possible, including stages, timing, and scope. This helps the borrower stay organized and on track, and it provides the lender with a roadmap for draw releases. Confusion and delays are minimal when both borrower and lender are on the same page from the beginning.

The budget must provide as much detail and granularity as possible, including stages, timing, and scope. This helps the borrower stay organized and on track, and it provides the lender with a roadmap for draw releases. Confusion and delays are minimal when both borrower and lender are on the same page from the beginning.

The budget should avoid large catch-all categories (e.g., labor) as a single number at the bottom of the repair list. A large category like that does not give the borrower or the lender a sense of how much labor should be included per draw. The result could be that no money is released for labor until the end of the project, creating a problem for the borrower, who will likely need to pay for labor on a weekly basis. To avoid these types of scenarios, the budget should label each stage, show the progression of the project, and what materials and labor belong to each line item and stage.

Large items, such as electrical and plumbing, should be separate line items for both final and rough states. Rough stages of construction have significant costs. By differentiating these stages in the budget, borrowers will be able to receive draw funds more timely and efficiently. Generally, rough stages of electrical and plumbing need to be completed and inspected before walls can be erected. If the line items are not broken down between rough and final, the borrower will not be reimbursed for the rough stage of the work until much later, when the final finishing of these items is complete.

Setting Borrower Expectations

Before closing, the lender must ensure the borrower understands that draw releases will not be issued until a line item is 100% complete. It makes it difficult for both the lender and the borrower when several line items are only partially finished. If the budget is broken down precisely enough, this problem can be avoided.

It is important for the borrower to know what “100%” means. For example, a lender may only release draws for installed materials rather than advancing for supplies that are bought but not affixed to the property. Releasing draw funds for uninstalled materials poses a significant risk to the lender, so funds are not released until the materials are actually installed, inspected, and completed in a manner satisfactory to the lender.

Additionally, the borrower should understand they cannot arbitrarily change the scope of the work. For example, if the budget includes dollar amounts for a finished basement, the borrower cannot decide they will not finish the basement. Presumably, the appraiser used the value-add of a finished basement to arrive at the after-repair value, and it’s likely the after-repair value was the basis for the loan amount. If the basement is not finished, the property will be less valuable than originally planned. Then the borrower may end up underwater on the loan and the lender will find itself undersecured.

The Importance of Inspections

Once the budget is in good shape and agreed upon by the inspector, borrower, and lender, releasing funds during the rehab process should be fairly simple. The role of a pre-closing inspector cannot be understated. The lender relies on an independent third-party inspector to give an honest, unbiased opinion on the work to be done and the work that has been done. The inspector needs to be well-versed in a wide variety of trades and costs.

More than a “visual” inspection is required. For example, the inspector needs to turn on appliances to ensure they are operational, test the HVAC systems, look inside electrical boxes, examine roofing, etc. Nothing should be beyond scrutiny. At the conclusion of each phase of inspection, the inspector should provide detailed inspection reports and pictures of the completed work, which should clearly relate to the original inspection report.

Release of the Funds

The lender needs to be careful with the logistics of the release itself. Many clients request to receive their draws by wire. It is highly recommended for the draw to be made only to the borrower and not to a third party.

If the draw is made to a third party, the lender must have the written permission of all parties to the loan agreeing to the disbursement to the third party. There have been instances where one member of a company directs the disbursements to an entity that only that member has an interest in, to the detriment of the other members of the borrowing entity. This becomes a problem when the other members do not benefit from the disbursement, and it could expose the lender to liability for disbursing to an entity that is not part of the loan.

Disputes occur frequently between co-borrowers, and a prudent lender does not want to get caught in the middle. Further, it should go without saying that with wire fraud at an all-time high, lenders should not send wires without independent verbal verification of all wiring instructions they receive by email.

Preventing a Mechanic’s Lien

Lenders must always keep in mind the possibility of a mechanic’s lien. A mechanics’ lien can be filed by someone who has done work on the property; the lien becomes an encumbrance on the title to the property. Every state has statutes that give workers the right to file these liens when they have done work to improve the property and have not been paid. Although the process differs by state, the right exists and can become a major headache for both the lender and the borrower. Accordingly, it is incumbent upon the lender to make sure the borrower is paying the general contractor and laborers for work that has been completed.

One way lenders can avoid a mechanic’s lien is to urge borrowers to ensure the general contractor includes a waiver of liens in the original contract. The waiver prohibits the workers from filing a mechanic’s lien against the property. On small projects, however, this may be difficult to achieve. Another way to avoid a mechanic’s lien is to require a lien waiver.

Before releasing the last draw, a lender may require a lien waiver from the contractor, allowing the owner of the property to be relieved from the obligation to pay downstream laborers the contractor failed to pay. The lien waiver provides that all subcontractors have been paid and that they waive any claim to file a lien waiver. In this way, the property owner is relieved of any future possibility of a mechanic’s lien.

Once a mechanic’s lien is filed, it either needs to be settled, paid, or successfully challenged before title to the property can be cleared. Note that every state has a technical set of rules regarding the filing of mechanics’ liens that set specific time limits, amounts, and notice requirement. Failure to follow these steps can leave the laborer without a valid lien.

The draw process on a rehab project can be complex or easy—it all depends on the preparation done before the loan is closed and the borrowers’ ability to stick to the budget and keep the project moving in an efficient and organized manner. The more preparation and discipline applied during every stage of the process, the more likely the project is to succeed.

Leave A Comment