Several converging factors are making office-to-multifamily projects more appealing for investors and capital providers. Here’s what you need to know.

The onset of the pandemic and the subsequent years brought several market realities to light. One is the need and demand for housing virtually everywhere in the country. The other reality, particularly in light of the work-from-home phenomenon, is the U.S. simply has too much unwanted office space.

Housing prices have reached levels no longer attainable for many young adults, and the market for decent rentals is often competitive, particularly in areas close to employment centers. Multifamily occupancy, rent growth, and development surged across most U.S. markets, fueling investor appetite and asset values. The pace of the expansion has since cooled, but the sector remains healthy, with absorption back in positive territory, vacancy at 5.1%, and rents at a record high of $2,184, according to a Q3 2023 CBRE report.

Even more telling are long-term construction trends, which have skewed in favor of single-family homes versus denser quarters. According to the Bipartisan Policy Center, 8.4% more single-family home permits were awarded between 2000 and 2021 than the historical average of the prior 40 years. At the same time, permits for housing with five or more units declined by 16.4%.

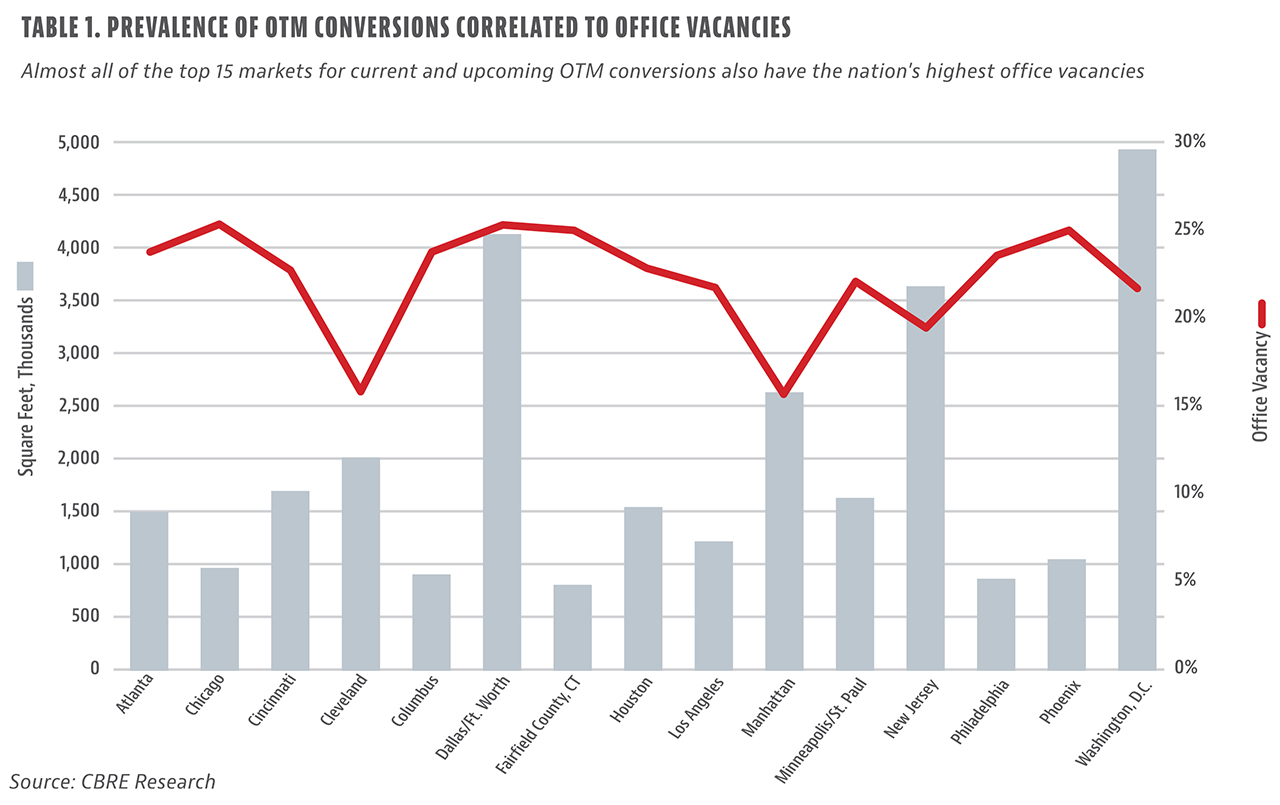

Compare that to the office sector, depicted in Table 1, which is undergoing a massive reset as the definition of the workplace evolves. Companies have been shedding unused space for several quarters, resulting in sustained negative absorption and vacancy hitting a 30-year high of 18.4% by third quarter, with a mere 40 bps difference between downtown and suburban offices. Conversely, the margin between asking and taking rents is getting wider, while tenants continue to exhibit a preference for smaller leases and Class A space. All of this is making it harder for office owners to generate enough net operating income (NOI) to service their debt. According to recent studies, U.S. office values could decline by as much as 30%, or more than $500 billion, by the end of this decade.

There’s a reckoning coming for the office sector, and a bank of underutilized and obsolete Class B and C office assets will be left in its wake.

Given these conditions, it would make sense to turn that unwanted office space into housing—in theory. The truth is that despite the perfect cocktail of multifamily versus office fundamentals, the rate of office-to-multifamily (OTM) projects has changed little during the past 10 years. During the past two decades, OTM conversions have accounted for just 1% of overall multifamily deliveries. With much of that product at the upper end of the market, the OTM conversion strategy hasn’t done much to help address the nation’s housing crisis.

A Shifting Tide Is Redefining City Centers

The problem with OTM is office buildings aren’t always good candidates for conversion. Turning offices into apartments isn’t a simple matter of sectioning off space. These buildings often have centralized plumbing, electrical, and HVAC systems that must be overhauled to accommodate individual units with kitchens and bathrooms. Office buildings’ deeper and wider floorplates also require creativity to allow for natural light and other necessities expected in multifamily units. In addition, myriad building codes and requirements can add to the cost and timeline of the conversion project.

For this reason, it’s tough to justify a conversion without focusing on high-end properties in urban cores, employing a unique approach, or both. In San Diego’s Gaslamp District, for instance, one sponsor bought a semi-vacant mixed-use building for $8.2 million in 2019. It then converted three floors of former office space into 27 microunits averaging 336 feet and renovated the existing restaurant on the ground floor. The sponsor implemented a high-end marketing strategy, banking on the success of a new office and technology campus rising across the street. The project has been completed and is currently undergoing lease up.

The other issue is that, by now, many of the viable assets in major downtowns have already undergone the process—take Lower Manhattan’s post-9/11 resurgence or the fruits of Los Angeles’ Adaptive Reuse Ordinance, for example. As conversion opportunities shrink and migration trends move away from primary markets, investors and developers are looking to infill and suburban locations for options. The type of available office product prevalent in these markets—older vintages with smaller floorplates, campus-style office parks with parking, and shorter buildings with smaller cores and operable windows—is also physically and financially conducive for conversion to multifamily.

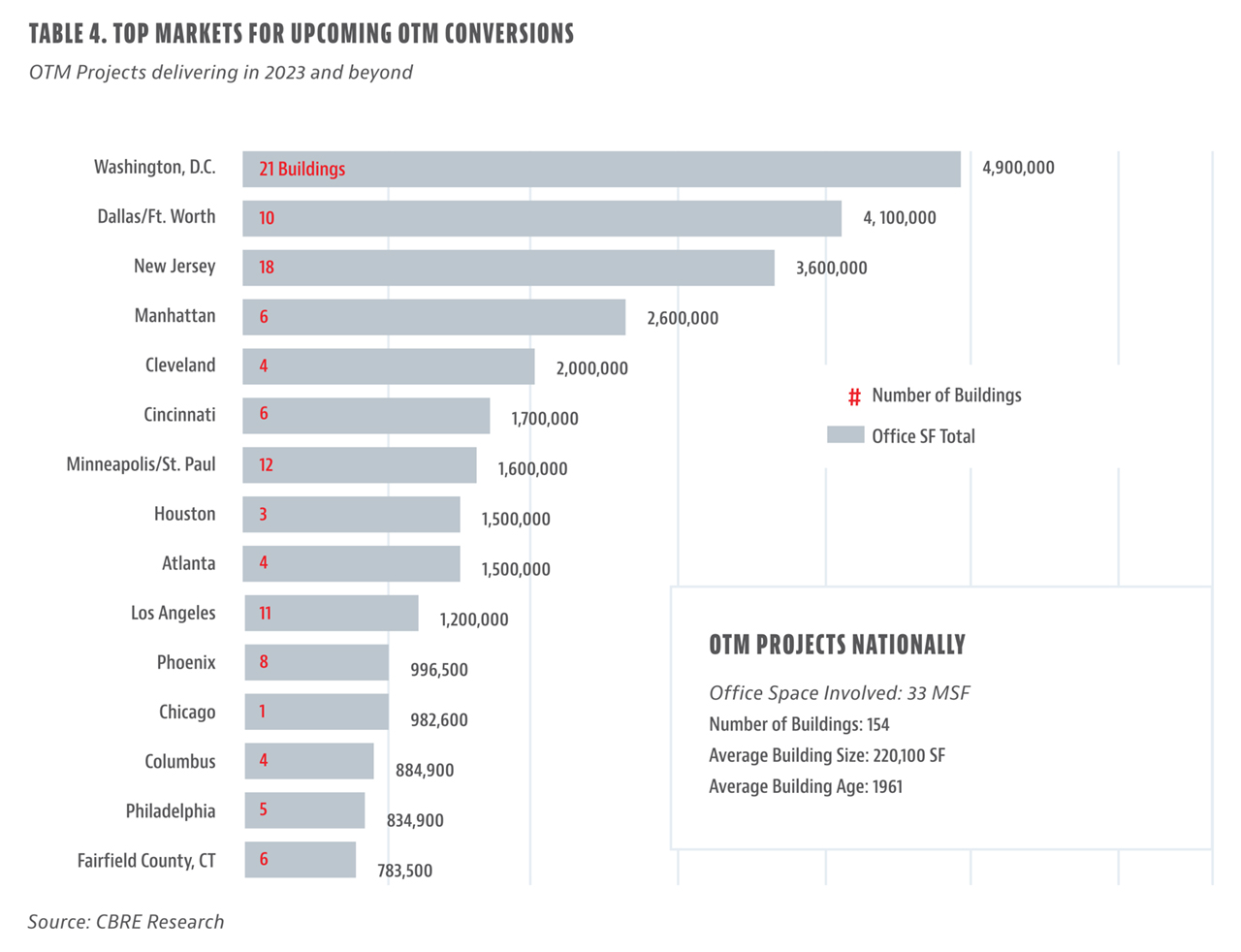

That helps to explain why a growing share of conversions are in areas traditionally considered secondary and tertiary markets. Primary, gateway markets accounted for five of the top 10 cities with the most converted apartments in 2020 and 2021, continuing a longtime trend. In 2022, however, Los Angeles was the only major city on the roster, with locales like St. Louis, Missouri; Kansas City, Missouri; Tucson, Arizona; Kissimmee, Florida; and Alexandria, Viriginia dominating the list. And, according to Rentcafe’s analysis, Tier I markets account for just four of the top 20 cities for future conversions.

These trends are predicted to continue as the strategy gains steam and investment capital flows to more attractive markets. For OTM projects, these are markets where current and projected demand and rent growth for multifamily is higher than for office space.

A Rallying Cry for Civic Leaders

Vacant commercial buildings are also a bane for local governments that rely on property taxes for revenue. A reduction in the tax base means there’s less capital available to fund public services, further reducing a market’s prosperity. Turning an underutilized office asset into housing can both boost the property’s value and create an influx of residents to help support local businesses and offset lost tax revenue. Yet years of conversion trends have shown that the math on the types of OTM projects that would help transform cities won’t work on a massive scape without public involvement—and investment.

Recognizing that the same zoning rules and regulations that helped cities manage sprawl in the past are now hindering their ability to adapt and evolve, municipal and state officials are aggressively trying to address the crisis. Public leaders everywhere are introducing legislation and initiatives to make conversions more attractive to developers. Several cities and states are offering new tax abatements, tax credits, grants, loans, and other incentives to promote OTM conversions. Others have allocated funds for future programs or are conducting studies on how to stimulate OTM activity in their towns.

Officials are also leveraging tools that are already in place, such as historic tax credits, tax-increment financing, and low-income housing tax credits. Existing programs are being adjusted and expanded, with officials streamlining approval processes and easing certain regulations to remove monetary and bureaucratic hurdles, rezoning areas to allow for more and denser residential product, reducing the age cutoff of applicable buildings for certain programs, and expanding the programs’ reach beyond core business districts to infill and outlying neighborhoods.

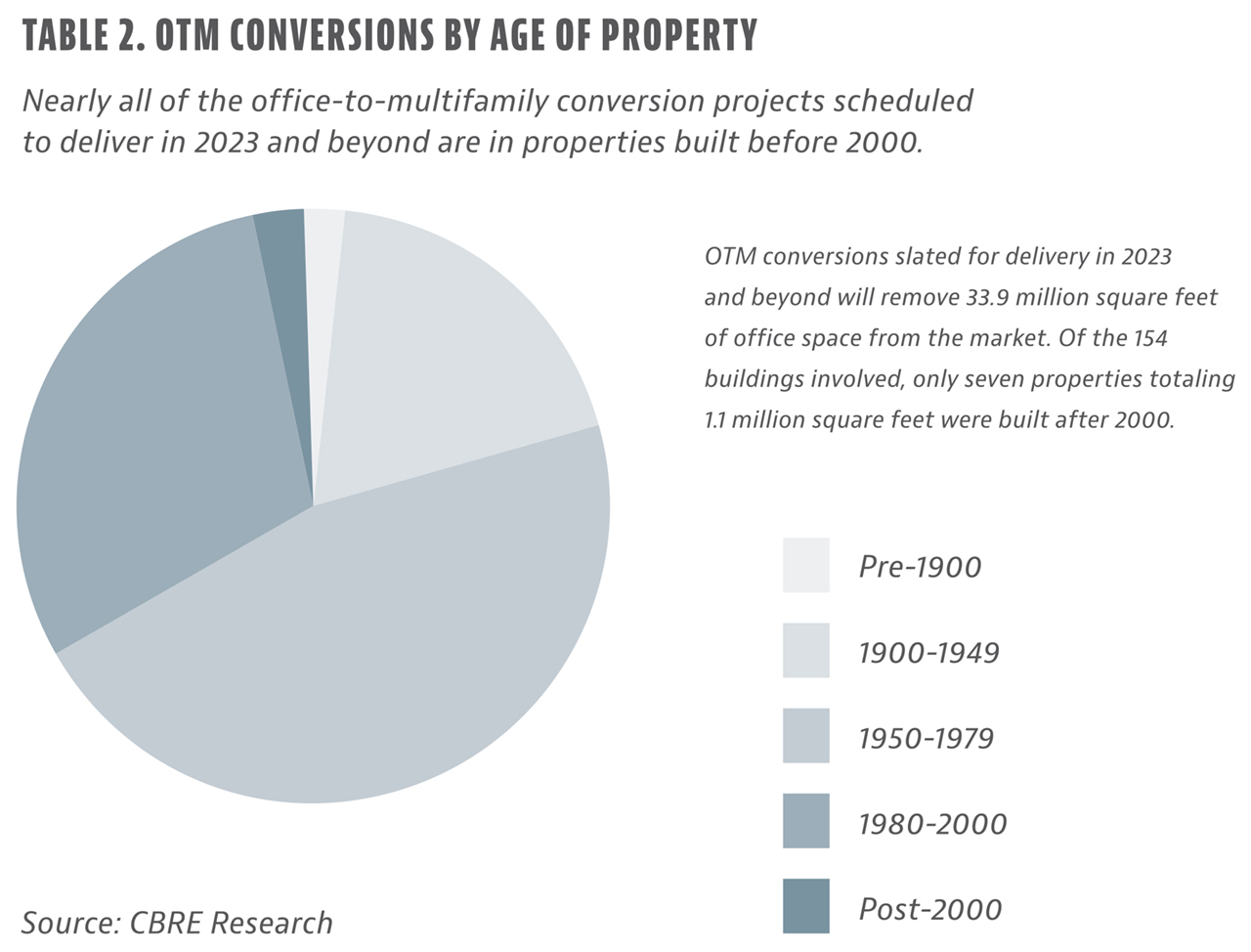

Federal-level activity is also promising. Efforts to address the nation’s housing crisis are intensifying, and OTM conversions are a large component. In January, sponsors introduced a new version of the Revitalizing Downtown Act, which would provide a 20% tax credit on qualified office conversions of properties more than 25 years old. Such bills support trends indicating that nearly all currently scheduled OTM projects are on properties built before 2000, shown in Table 2. HUD has also released a notice of funding opportunity for a study of post-pandemic OTM conversions.

In October 2023, a dedicated working group formed by the Biden-Harris Administration released a 54-page guidebook laying out new and existing opportunities in which the federal government can facilitate the conversion of office space to affordable housing, including reduced development costs and identifying underutilized federal assets that are well-suited to conversion.

Existing federal programs can also help support OTM conversions. These include longstanding programs like historic tax credits, new markets tax credit (NMTC), low-income housing tax credits (LIHTC), tax increment financing, and opportunity zone incentives. Also relevant are initiatives that would help subsidize energy-efficient, sustainable retrofits and development, like the EPA’s $27 billion Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund and renewable energy tax credits.

Multiple incentives and financing tools can also be combined to help offset the cost of OTM conversions and create market-rate and affordable units. For instance, by combining a state credit and federal historic tax credits with NMTCs or LIHTCs, an investor with a qualifying OTM conversion can cover as much as half of their construction costs—effectively increasing the project’s equity component and ultimate NOI.

It’s important to note, though, that many of these programs come with caveats that investors and lenders must consider, such as minimum hold periods or the inclusion of affordable or workforce housing.

The surge of public support for OTM suggests conversions may not just become easier, but even encouraged, throughout much of the country. As OTM conversions become more understood and commonplace, so will opportunities for investors and providers of capital.

Private Debt Can Fuel OTM Conversions

Many traditional lenders and investors view conversions as risky endeavors; rising interest rates and the stricter financing climate put an even bigger damper on the strategy. The nuances of OTM conversions, however, make them a natural fit for private real estate lenders.

An OTM conversion is the exact type of transitional situation that would qualify for a bridge financing. Sponsors have long been using bridge loans for value-add projects, making capital improvements to upgrade or reposition underutilized or obsolete properties. Because these deals are rarely straightforward, bridge lenders are used to evaluating transactions on a case-by-case/market-by-market basis.

Private lenders, most of which operate in the middle market, are also familiar with the type of real estate suitable for conversions. Although headlines have focused on the transformations of large office towers to luxury apartments in the nation’s top CBDs, there are far more OTM conversion opportunities among older, smaller buildings outside of major cities. These structures also have smaller floor plates, working windows, and other features that are conducive for residential conversion.

The key is to find markets with greater demand for apartments than for Class B office and properties that would lend themselves well for residential conversion. Research shows that in most markets, it’s older Class B/C office assets. These assets are smaller in size than modern buildings, but larger in number—and market impact. One JLL study reported that since the pandemic, nearly 80% of overall negative absorption has been in buildings delivered before 1980. Considering the average age of U.S. office buildings is 53 years, that equates to a tremendous amount of reuse opportunities.

The construction period for conversions is roughly three times faster than for new builds, reducing time-to-market by as much as two years. That corresponds with the average term of bridge loans, which typically max out at three years after extension provisions. Conversions can also cost 20% to 40% over new builds, given the reduced timeline and ability to reuse building materials. Both factors help to mitigate risk in the deal while effectively increasing returns. An added benefit is that conversions are typically more environmentally friendly than construction.

The success of any project depends largely on the capabilities of the sponsor, so it’s important for lenders to be comfortable with the borrower, its resources, track record, and business plan. By the time a sponsor approaches a bridge lender for an OTM project, it should have already completed a tremendous amount of due diligence, market research, and financial and legal analysis, as well as any third-party environmental and engineering studies. Preliminary approvals, entitlements, and permits should be in place. If public funds are being used, the sponsor will likely have submitted all the necessary documentation in advance, because the approval process can be long and complicated, and some subsidies don’t kick in until after occupancy. If the sponsor doesn’t have a firm grasp on all facets of the project, lenders will perceive greater risk in the transaction.

For lenders, the risks associated with conversions are similar to construction and can be addressed through underwriting, contingencies, interest reserves, and other mitigants.

The inclusion of public subsidies shouldn’t be a deterrent either. In fact, subsidies often work in sponsors’ favor since they can help the project’s overall success. For instance, Red Oak has successfully provided bridge financing on a few Washington, D.C., multifamily rehabilitations under the federally funded Housing Choice Voucher Program, which provides partial to fully guaranteed subsidized rent to landlords. Some of them had an added bonus of being in an opportunity zone.

Any caveats associated with public funds, though, must be factored into the deal terms. For instance, many public programs require minimum hold periods, so the sponsor’s exit plan will likely include permanent financing or another form of payoff, rather than a sale. A borrower might also use a bridge loan to fund a project while its application for HUD financing is being reviewed—a process that can take six months or longer. If tax credits are being utilized, often the property can’t be subject to a lien. In these cases, the collateral for the bridge loan isn’t the physical asset. Rather, it’s the expected tax credits. The loan provides the necessary capital to complete the conversion. Upon stabilization, the sponsor will repay the bridge loan using the interest generated by the expected tax credit investments.

Momentum Is Building

Although conversion activity this cycle has slowed slightly from the initial surge earlier in the pandemic, a convergence of factors will make OTM projects more appealing for investors and capital providers:

- Nearly one billion square feet of U.S. office space is currently vacant. With more than 100 million square feet under construction, vacancies will likely increase with deliveries. The sustained reduction in office demand and tenants’ continued flight to quality will render millions of square feet of older product obsolete.

- Office is accounting for a growing share of overall delinquencies. Many loans are coming due in the next couple years and rising debt servicing costs continue to pressure borrowers. Owners will need to decide whether to refinance, get the assets off their balance sheets, or put capital into improvements. Given the tighter lending climate, the latter two options are more likely.

- Although property types like hotels and industrial are more conducive to residential conversions, the window to buy them cheaply has passed and investor appetite remains high. As office values will fail to keep up with their counterparts, they will remain the primary target for reuse.

As of July 2023, 122,000 units worth of new conversions were under way, with 45,000 of them in former office buildings, per Rentcafe’s analysis. Future conversions are expected to grow by 63%, and OTMs will comprise a greater share of these projects as more sellers adjust their valuations.

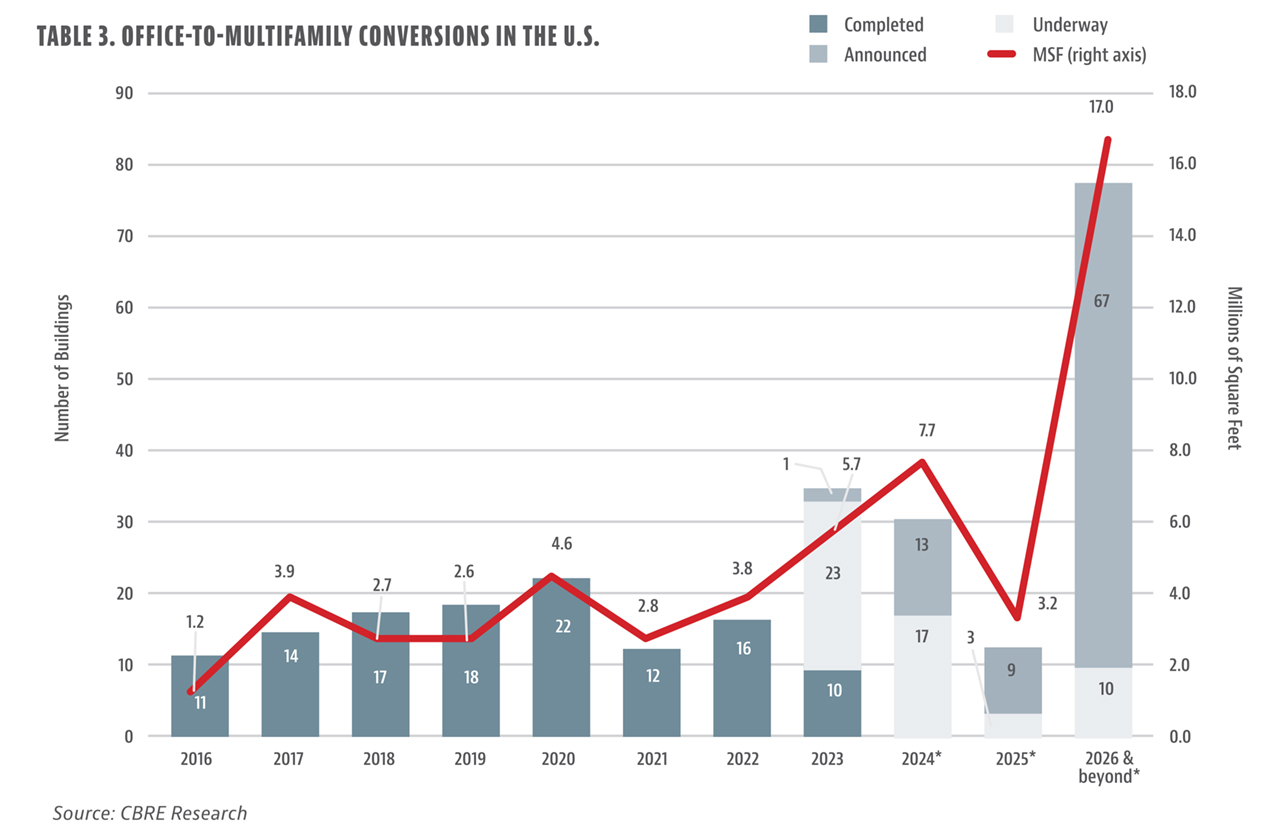

A more recent report from CBRE supports this theory (see Table 3 above and Table 4 below). About 100 office conversions are slated for delivery this year alone, up from a longtime annual average of 41. Another 201 conversions have been started or announced. These projects account for some 60 million square feet of space, or 1.4% of U.S. office inventory—a 20-basis-point uptick from last year. As expected, the markets with the most conversion activity not only have higher-than-average vacancies but also higher numbers of older buildings.

OTM projects make up 118, or 48%, of all upcoming conversions, with plans calling for 21,000 units to be created in the coming years. Office-to-mixed-use conversions account for an additional 18% of total projects. Most of the office conversions are thus far scheduled for 2025 or later, just in time for the expected rebound of both the multifamily market and broader economy. If the market demand and financial specifics are favorable, a strong sponsor with an OTM conversion project can be a great candidate for a bridge loan.

Leave A Comment